India: A History of Creativity and Struggle from the World's Largest Audiovisual Producer

- AVACI

- Mar 19

- 5 min read

With the official recognition of the Screenwriters Rights Association of India (SRAI) as a Collective Management Organization under the Author’s Rights Law, it is worth reviewing the arduous path that screenwriters had to take to achieve this goal.

Although it may seem like a repeated fact, it is important to remember that India, a linguistically and culturally diverse country with 1.45 billion inhabitants—the most populous on the planet—hosts a vast and complex audiovisual industry. In a country with 20 federal states and 28 official languages, film production spans at least 22 different languages. Of the more than 1,300 films produced annually, only about 500 are made in Hindi, the official language. Other regional languages, such as Telugu, have even gained international recognition, as demonstrated by the song "Naatu Naatu" from the movie "RRR", which won an Oscar in 2023.

Mumbai is the hub of Hindi-language film production, while in the south of the country, between 300 and 400 films are produced annually in four different languages. The eastern region, near the Chinese border, also has a thriving film industry in Bengali. However, India’s capital, New Delhi, is not a center for film production. Amid this vast diversity, audiovisual authors' rights have been the subject of a long-standing struggle.

“Naatu Naatu”, RRR (S. S. Rajamouli, 2022)

Historical Evolution of the Audiovisual Sector in India

In 1957, Indian legislation recognized the rights of authors, composers, and lyricists. However, this law was largely unknown to most creators, and only a few renowned musicians were able to negotiate their rights with producers. The vast majority of authors received no royalties, with contracts limited to a single payment or commission.

During the 1960s, the Indian Performing Rights Society (IPRS) was created to equitably distribute royalties: 50% to the publisher, 25% to the author, and 25% to the composer. Over time, however, record labels took full control of these societies, relegating authors to a secondary role. This situation prompted authors to fight for their rights, but industry resistance made it a difficult battle.

Apu Trilogy (1955-1959), directed by Satyajit Ray

In 2010, new regulations granted audiovisual authors the right to receive royalties for the exploitation of their works. However, producers and other organizations opposed this, ultimately excluding authors from the negotiation process. Subsequent modifications to the law established that if an author did not transfer their rights to the producer or record label, their contract would be considered illegal. Additionally, royalties were deemed inalienable, except in cases where they were transferred to a collective management organization or the author's legal heirs.

In 2013, representatives of India's audiovisual community traveled to Europe to meet with various collective management societies, such as DAMA, to gather information on rights protection models. Upon their return, they began forming their own organizations, but they faced numerous obstacles, including limited access to legal advice and challenges in legally reclassifying screenplays as "literary works."

Obstacles and Resistance

Despite legislative advances, implementation was delayed due to bureaucratic reasons, such as minor wording changes in regulations. While awaiting final legal approval, the Screenwriters Rights Association of India (SRAI) began managing authors' rights collectively. However, a lack of financial support and corporate pressure continually hampered this process.

Currently, it is estimated that India has around 25,000 active screenwriters. The author’s rights law extends rights for 60 years after the author's death, allowing thousands of heirs to access royalties. In total, approximately 40,000 people could benefit from these rights—a significant number in a country with high youth unemployment.

The Impact of TV and Streaming Platforms

The television sector has historically played a key role in India's audiovisual industry. With eight Hindi-language channels and at least ten daily programs on each, the demand for screenwriters is high. Each channel is estimated to employ between 40 and 50 screenwriters, meaning around 450 screenwriters work daily in Hindi television, with another 500 waiting for an opportunity to break into the industry.

Many of these screenwriters face exploitative contracts and unfair agreements. A lack of knowledge about their rights and fear of losing their jobs often forces them to accept unfavorable conditions. To counter this situation, SRAI members have organized workshops across India to educate screenwriters about their rights. Streaming platforms have introduced another challenge: the imposition of Non-Disclosure Agreements (NDAs) that can facilitate idea theft without legal consequences. Although authors are warned about the risks of these contracts, many sign them out of fear of being excluded from the industry. Additionally, some production companies use legal strategies to intimidate screenwriters by filing lawsuits in remote locations, where the cost and difficulty of appearing in court deter authors from defending their rights.

Kill (Nikhil Nagesh Bhat, 2023)

The approval of SRAI is the result of a long process that began in 2012, when India's author’s rights law was amended. Following this amendment, a group of screenwriters decided to form the country's first collective management organization. However, SRAI’s application remained stalled in government for eight years without official approval. During this time, the lack of legal recognition created problems for royalty collection and complicated relationships between creators and large audiovisual corporations.

Bridges and Support for SRAI

One factor contributing to the delay in SRAI’s approval was the existence of multiple collective management societies in different repertoires, complicating royalty payments to authors. To address this issue, the Indian government developed a "one-stop window" system to centralize royalty collection and distribution.

Despite the vast expansion of its audiovisual industry and the global influence of its cinema, screenwriters and other authors lacked an effective legal framework to receive fair royalties. After more than a decade of waiting since the 2012 amendment to the author’s rights law, the Indian government approved the operation of the SRAI, marking a significant advancement in creators' rights protection.

Of course, the process of securing SRAI's recognition was not easy. Since its founding in 2012, the society faced numerous bureaucratic challenges and corporate resistance that made royalty payments to multiple societies difficult. However, a court ruling in the NOVEX case allowed Collective Management Organizations to operate without mandatory registration, as long as they complied with the author’s rights law. This facilitated SRAI’s consolidation and its official recognition as the entity responsible for managing screenwriters' rights.

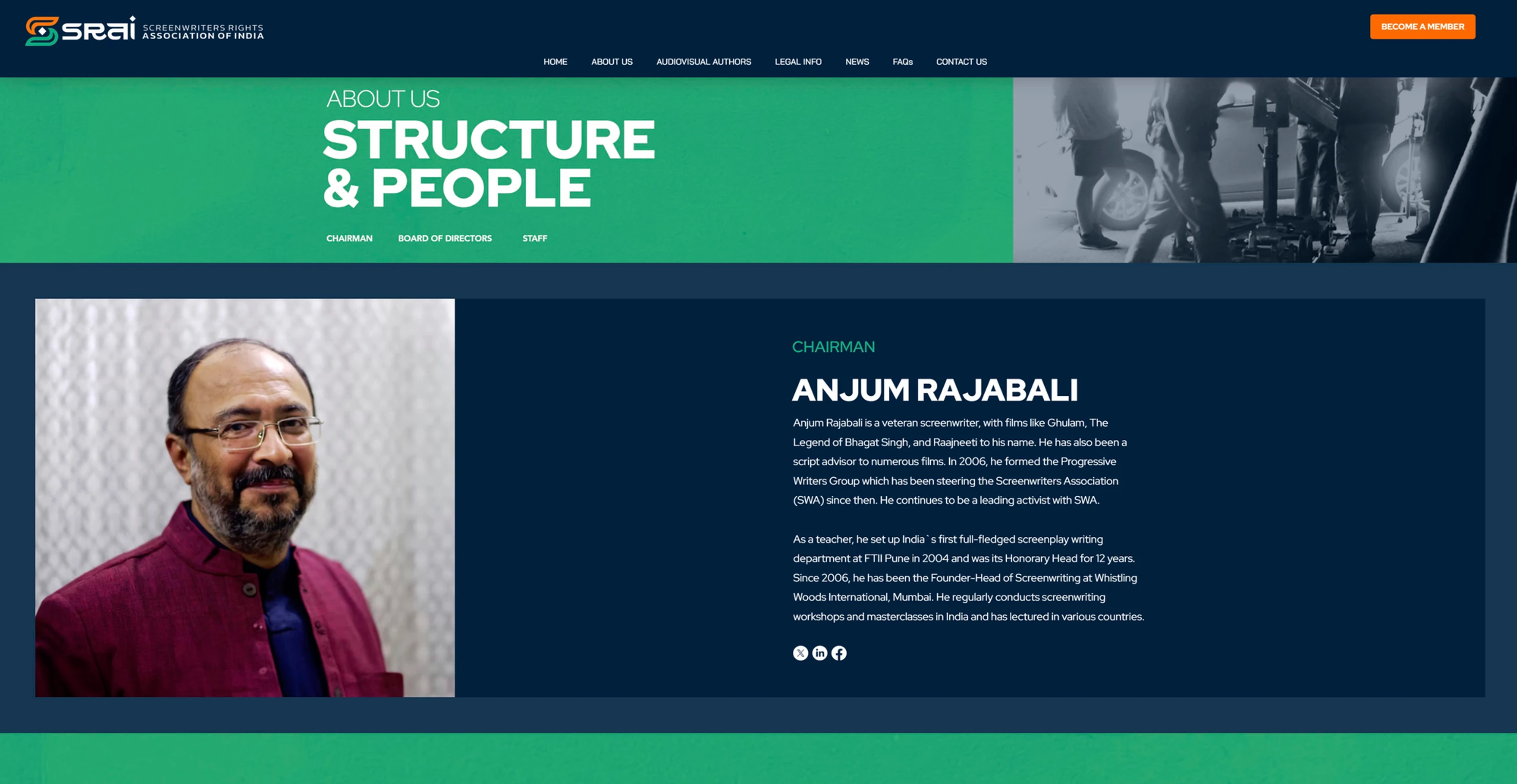

Anjum Rajabali and Vinod Ranganath, SRAI authorities

The Indian royalty system has particularities that SRAI must navigate. By law, any royalty collected by a screenwriter must be shared equally with the producer. This means the society must maintain a balance between both groups in its governance structure, ensuring equal representation of authors and producers on its board. Another major challenge is the country’s linguistic diversity. Since works can be registered in up to 17 different languages, SRAI has proposed that titles be recorded in English or Hindi to streamline management.

Since receiving government approval, SRAI has launched a nationwide membership campaign, aiming to recruit between 25,000 and 30,000 members, including active screenwriters and heirs of deceased creators.

With the unwavering support of the International Confederation of Audiovisual Authors (AVACI), SRAI has established agreements with other international Collective Management Organizations to strengthen its structure. In this context, collaboration with entities such as Directores Argentinos Cinematográficos (DAC) and Sociedad General de Autores de la Argentina (ARGENTORES) has enabled the training of SRAI members. One of the most crucial training tasks for SRAI’s formation was learning to manage AVSYS AI, an Integrated Operating System for Audiovisual Works designed by the Federation of Latin American Audiovisual Authors Societies (FESAAL) to oversee and execute all operations of an audiovisual rights management society. The Argentine organization representing audiovisual directors also played a role in designing SRAI’s final website and logo.

The establishment and official recognition of SRAI mark a milestone in India's audiovisual industry, providing creators with a solid structure to defend their rights. With support from international organizations under AVACI, SRAI will ensure the fair distribution of revenues generated by authors. This is a crucial step toward equity and recognition for screenwriters in one of the world's largest film industries.

Comments